| |

Search |

|

|

|

|

|

|

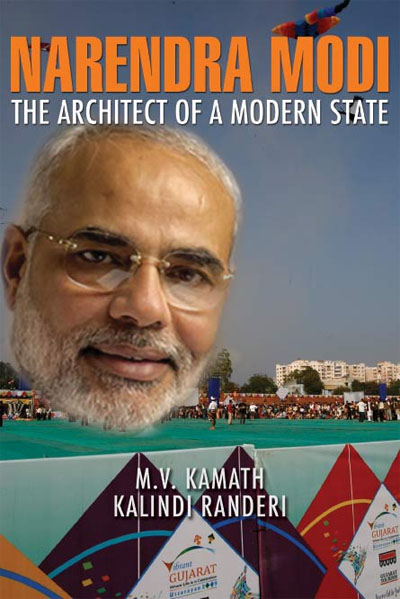

Narendra Modi:

The Architect Of A Modern State

MV Kamath and

Kalindi Randeri

Rupa

298 pages |

Teesta Setalvad

It

is the title of the book that is apt. In this book, Narendra Modi, whom

the supreme court of India has, in writing described as having the

qualities of a “modern day Nero” (April 12, 2004) is equated with the

credit for fashioning what is, according to the two authors, the ideal

modern nation state. Recently published, and well timed with the ongoing

fifteenth Lok Sabha elections it is designed to apply the final gloss on

a vast and minutely planned promotional exercise.

The

term nation state, even without the sharply fascist edge given by Hitler

has been controversial. The fact that the title of the book chooses this

to define Modi’s project and not the Indian Constitution’s vision of a

secular democracy is telling. Hardened commentators, if not academically

qualifies political scientists, have chosen to define a nation state as

a territorially defined entity principally of the same kind of racially

compatible cultures and peoples. And therein lies the crux of the

argument. Modi’s ideal state is a construct where the qualities of a

state are defined by a thrust that is inimical to our Constitution.

Difference, dissent, accountability and transparency are simply not

acceptable to a formula for governance that believes in half truths

peddled through a screened and orchestrated effort, nationally at least.

The attempt is to promote a persona to man such a state, who is not

challenged, riled or ridiculed as his compatriots in the political class

are, either through hard facts or informed criticism. Modi does not

speak at accessible press conferences where the media can shout inane

questions at him though even Advani, our prime minister in waiting, has

to allow himself this indignity in the interests of democracy. He roars

and threatens, euphoric with the crowd of his supporters at least 40

metres away. Now an iron railing will guard this self-declared architect

of a modern state in case a chappal or shoe whizzing past blurs

the image considerably. Through this his place in the nation state’s

future is being carved. Little surprise then, that the stinging

aggression of a Karan Thapar (July 2007) is unlikely to cause Modi to

stutter again.

In

large part this book enlists for the reader of the economic wonder that

is Gujarat today. In the chapters that add the personal touch, it is

the magic of India’s toiling ascetic turned politician who was born to

serve --not govern—that is woven by the authors, another attempt to

shame his critics. Not just the tremors of the vibrant Gujarat summit

and the Nano miracle that had the Indian corporate first family –the

Tatas – join the Ambanis and the Mittals in the general backslapping of

Modi, but the slogans of water water everywhere…….., jobs galore, and

safety and security within the state are enlisted page after page for

the fan to devour.

The

book does not attempt any critical distance and while, In Gujarat, the

print media continues its job, probing of the state’s claims to a

glittering Gujarat, the book is a careful collation of the state’s press

releases, uncritical and eulogistic. Look at this. While figures

released by Modi in January 2009 (about the Vibrant Gujarat summits in

2005 and 2007) peg the total proposed investment inflow from the 229

MoUs signed during the 2005 VGGIS at Rs 106,161 crore, his own

government has admitted (RTI applications sought from the Industries

Commissioner) that investments, both commissioned and under

implementation, totalled only Rs 74,019 crore. This means that while

Modi boasted of a spectacular success rate of

63.5 per cent in terms of implementation of proposed investments made

in the vibrant summits of 2005 and 2007, the state has not been able to

get even 25% of the so called MOUs implemented even in the primary

stage. The Nano story is nothing short of scandalous. It was the

Times of India, Ahmedabad that exposed the twenty year

VAT-free run for the Tatas indicating that this lollipop at the Gujarati

tax payers expense, was the sub-text of the deal. The fine print of the

MOU revealed that the loan of Rs 9,570 crore offered at a meagre 0.1 per

cent interest will be repaid by Tata Motors only from the 21st year.

The

poor in Gujarat are not normally Modi’s concern and his exhortation of

the five plus crore population of his state is meant to douse the

rumblings caused by hunger, poor food security, joblessness and

displacement by the all consuming flames of a hate driven hindutva.

Only about 59.6 per cent of the rural children of Gujarat can read

the standard one text book as against an all-India average of 66.6% (Indian

Express December 21, 2008). According to the International Food

Policy Research Institute’s 2008 Global Hunger Index, Gujarat (placed in

the ‘alarming’ category) is ranked 69th alongwith Haiti, the nation

infamous for food riots. Similarly figures of electricity generation

and food production dished out by the state have been disproved by its

own official documents

and

the CAG annual report exposes Gujarat’s efficiency being none better

than other states when it comes to implementing schemes.

State legislatures in functioning democracies exist as legislative

bodies as also as deliberative bodies to question and debate a

government’s policy. In Gujarat the assembly, in 2006 and 2007 met for

just 23 days in a whole year, the lowest for the country. Journos are

rarely allowed inside Sachivalaya’s dep[artments, confined to the

canteen. None dare question the questionable in Gujarat.

What

then is this well timed volume is all about? At page 165 we have the

raison d’etre of the Kamat-Randeri enterprise. The authors callously

dismiss the fact that former parliamentarian, Ahsan Jafri made several

dozen calls for help before he surrendered himself to a mob that

butchered him, bit by bit. (Sixty nine others faced the same fate that

day at Gulberg society in a massacre that lasted a whole working day;

and a total of 2,500 persons, all Muslims over all of Gujarat between

February 28 and March 3, 2002). In a chilling justification why none

rushed to Jafri’s help, Kamath and Randeri write, “The common public can

ask why help was not given at the time when it was needed the most…The

plain answer is that anti-Muslim sentiments run deep in the hearts of

most Hindus in Gujarat…..quoting from an editorial from the Indian

Express that criticized Modi’s ways the authors gleefully say’

nobody in his wildest dreams could have imagined the kind of game that

Modi was going to play. He has played his game, won the match and won it

convincingly..’

This

forced consensus around Modi that this public relations exercise

promotes wishes us to forget not just the gory details of recent events

but how this man, at the height of a euphoria in 2002 even dared

threatened and bullied our media. “What insecurity are you talking

about? People like you should apologize to the five crore Gujaratis for

asking such questions. Have you not learnt your lesson? If you continue

like this, you will have to pay the price’ is what Modi had boomed to

Rajdeep Sardesai on December 15, 2002 in the first flush of his first

post massacre electoral victory. Six month earlier, the Indian

Express( June 11, 2002) has quoted him as saying that “ That

journalists who cover Gujarat… may meet the fate of Danial Pearl… Cover

communal riots at your own risk.”

This

then is the victorious, chilling sub-text of this biography. It is a

book that seeks to sell to the Indian elite a man who has dared to

re-model himself on a mini bloodbath. Over the chopped, brutalized and

burned bodies of the state’s Muslims in what was post independent

India’s ‘justifiable’ ethnic cleansing. A miffed Modi has on occasion

has dared say that Muslims in general have even forgiven him; and he

uses the appointment of SS Khandwawala as director general of police, as

the totem that sells the tale. But here, in this book there is no need

for the authors to even speak of the language of forgiveness or remorse

since for Kamath Randeri and many of their supporters, this is a small

price that India must pay.

For

these architects of hindutva India needs to accept this heavy

human cost if it needs to emerge, re-incarnated. The real tragedy is

that our general culture of impunity to perpetrators of mass crimes

committed with the connivance of the state finds for Modi otherwise

politically incompatible bedfellows. No wonder then that those among his

staunchest political opponents are therefore reluctant to puncture the

Modi mirage.

|